In the 1870s, the industry was transformed by the arrival of large, steam-powered sealing vessels, such as the steam barquentines Bear and Terra Nova, which could smash through ice packs to the heart of large seal herds. These large and expensive ships required major capital investments from British and Newfoundland firms, and shifted the industry from merchants in small outports to companies based in St. John’s, Newfoundland. By the late 19th century, the sealing industry in Newfoundland was second in importance only to cod fishing.

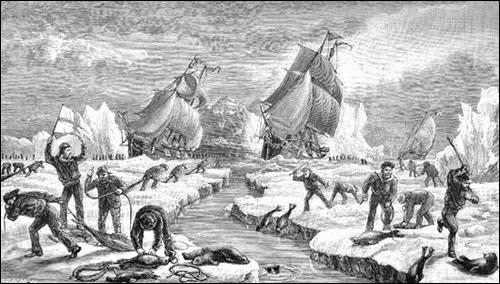

The Seal Hunt. By 1803 over 100 vessels, carrying 3,500 to 4,000 men, were engaged in sealing. Illustration by Percival Skelton. From Joseph Hatton and M. Harvey, Newfoundland, the Oldest British Colony (London: Chapman and Hall, 1883)

The seal hunt provided critical winter wages for fishermen, but remained harsh and dangerous work, marked by major sealing disasters which claimed hundreds of lives, such as the loss the 1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster involving the SS Southern Cross, the SS Newfoundland and SS Stephano.

After World War II, the Newfoundland hunt was dominated by large Norwegian sealing vessels until the late 20th century, when the much diminished hunt shifted to smaller motor fishing vessels, based from outports around Newfoundland and Labrador. In 2007, the commercial seal hunt dividend contributed about $6 million to the Newfoundland GDP, a fraction of the industry’s former importance.

1914 Sealing Disaster

Following is an historical account (Article by Jenny Higgins. ©2007, Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site) of what occurred in March 1914 to sealers who perished on the ice and icy waters off the coast of Newfoundland in separate incidents.

“The SS Newfoundland left St. John’s for the North Atlantic ice fields in March 1914, no one anticipated the hardships that lay ahead. Its captain, Westbury Kean, was accompanied on the hunt that year by his father Abram Kean, veteran sealer and captain of the SS Stephano. Although the two ships worked for competing firms, each captain had agreed to alert the other of any seals they spotted.

Frustrated by his inability to move and anxious to catch a share of the seal herd, Westbury Kean ordered his men off the ship the following morning. He instructed them to walk to the Stephano, believing the sealers would spend the night onboard his father’s steamer after a day of hunting.

Tired from the morning’s four-hour trek, unable to see the Newfoundland, and in a thickening storm, the 132 men were once again on the ice. The group spent the next day and night trying to reach the Newfoundland, but without luck. Some men, delirious, walked into the frigid waters and drowned; others were pulled back onto the ice by their companions, but often died within minutes. Westbury and Abram Kean, meanwhile, each believed the sealers were safely aboard the other man’s ship. Communication between the two vessels was impossible because the Newfoundland was not carrying wireless equipment. The steamer’s owner, A.J. Harvey and Company, had removed the ship’s wireless because it had failed to result in larger catches during previous seasons. The firm was interested in the radio only as a means of improving the hunt’s profitability and did not view it as a safety device.”

It was not until the morning of April 2 that Westbury Kean, surveying the floes through his binoculars, spotted his men crawling and staggering across the ice. Desperate to help, but lacking any flares, Kean improvised a distress signal to alert other vessels within the fleet. Of the 77 men who died on the ice, rescuers found only 69 bodies; the remaining eight had likely fallen into the water. The survivors were brought to St. John’s for medical care.

SS Southern Cross

While the sealers from the SS Newfoundland were stranded on the ice off Newfoundland, a second sealing tragedy was unfolding to the south. In early April 1914, the SS Southern Cross sank while returning from the Gulf of St. Lawrence. 174 men tragically died.

On March 31, the coastal steamer SS Portia passed the Southern Cross near Cape Pine, off the southern Avalon Peninsula. Although the Portia was headed for St. Mary’s Bay to wait out a worsening blizzard, the Southern Cross, low in the water with its large cargo of seal pelts, seemed headed for Cape Race. The steamer was not seen again, and because no wireless equipment was on board, communication with other vessels was impossible.

However, popular consensus at the time suggested that the ship’s heavy cargo may have shifted suddenly in the stormy waves and capsized the steamer. Whatever the cause, the sinking of the Southern Cross resulted in more deaths than any other single disaster in Newfoundland and Labrador sealing history.

Article by Jenny Higgins. ©2007, Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site