Hunting Methods: The Landsmen Sealing Operation

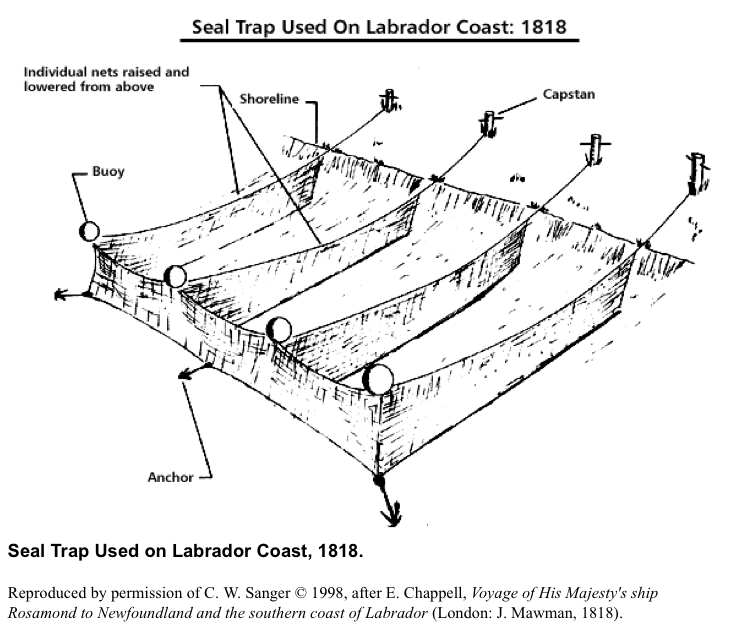

In order to capture harp seals from shore, the early inhabitants of northeastern Newfoundland and southern Labrador developed two principal techniques – the use of seal (or shoal) nets and seal traps (or frames).

As early as 1818, for example, the master of a British naval vessel on fishery patrol along the Labrador coast provided a detailed account of modifications made to a single seal net and the development of the seal trap. The traps were more commonly used in the more northerly regions where the seals travelled closer to shore in late fall and early winter.

Whole communities – men, women and children, all with fixed responsibilities – worked together to ensure the capture of the migrating herds. Although harp seals do not follow the shore line with the same intensity and regularity as they approach the more southerly areas of the island, they could still be caught in specially constructed nets. This procedure was used well into the twentieth century.

Seals could thus be captured from land bases with relatively little capital investment in a fashion that neither required the participants to leave home for extensive periods, nor forced them to face the risks associated with the larger-scale offshore seal fishery. The landsmen operation, carried on in the fall and early winter, added a valuable commercial opportunity to the seasonal round of activities.

The Vessel Operation

Towards the end of the 18th century, merchants and investors in St. John’s and the larger centres in Conception Bay began to support voyages in sailing vessels each spring in search of the newly formed whelping patches. By 1800 this large-scale commercial venture was well established.

The first sealing vessels of any real substance were fishing schooners designed for the fledgling Labrador cod fishery.

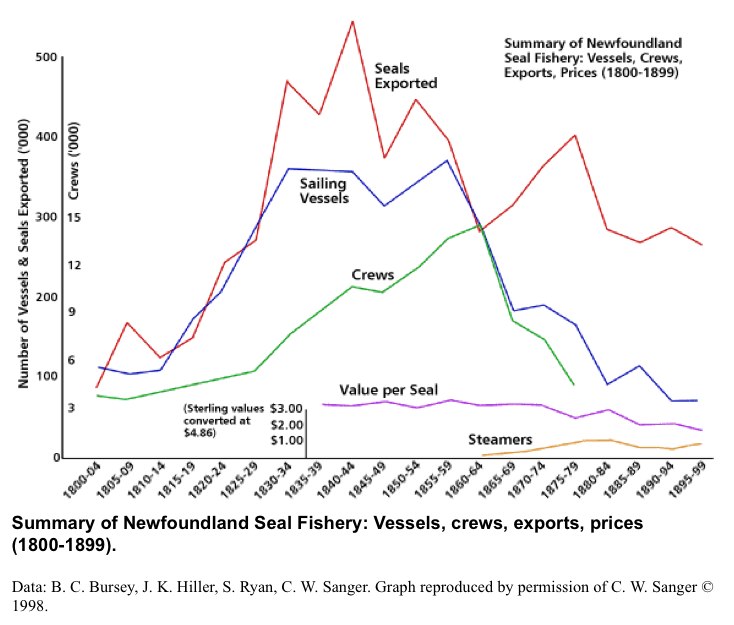

The success of these two complementary activities appears to have been rapid, as demonstrated by the increase in the number of skins (pelts) exported: from less than 5,000 in 1793 to 81,000 in 1805, 281,000 in 1819 and 687,000, the highest number ever reported, in 1831.

The growing importance of the seal fishery and its economic impact throughout the first half of the 19th century is indicated in the writings of Rev. W. Wilson. In 1866 he noted that the sealing vessels averaged from “fifty to one hundred tons, and were manned with crews of from twenty-five to forty men; while the interest of every individual to the north of St. John’s, from the richest to the poorest, was so interwoven with it, that its prosecution and results should cause more speculation, more anxiety, more excitement and solicitude, than perhaps does any single branch of business in any part of the world” (Wilson 276).

During the latter half of the 19th century the industry began to contract, partly because of a decline in the seal population caused by unregulated harvesting and the introduction of steamers.

After 1863 the owners and outfitters of the less efficient sailing vessels realized that they could not compete. Higher financial investments were required and the smaller outport merchants and entrepreneurs were gradually displaced. St. John’s emerged as the major residential centre for vessel owners. Fewer men and ships participated. The northern boundary of the sealing region shifted southwards to exclude the traditional sealing areas along the northeast coast.

By the late 1800s new forces were at work within the industry. Steamer owners hired experienced sealing masters from the more northerly communities to command their vessels; there was an attempt to have older ships sail for the ice from outports closer to the seal herd; and a more efficient transportation system (railway) enabled sealers from Bonavista and Trinity Bay settlements to obtain berths on the St. John’s steamers. These developments resulted in the sealing region spreading northwards again to include the growing Bonavista Bay North communities located between Greenspond and Newtown. By the beginning of the 20th century there existed two sealing regions, one centered in Bonavista Bay North and the other in St. John’s.

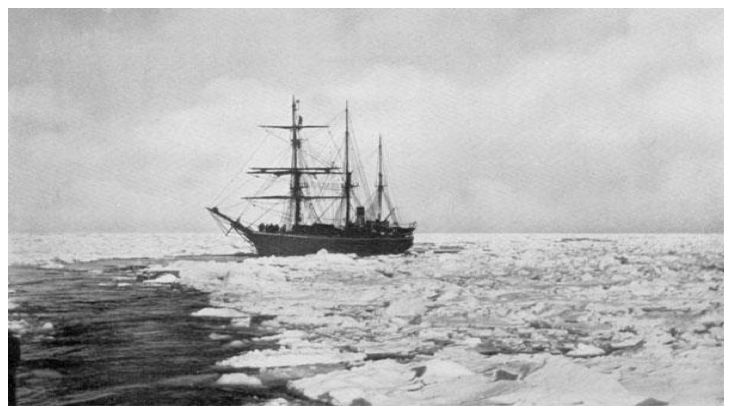

Sealing steamer S.S. Kite in the ice floes off northeastern Newfoundland,

Sealing steamer S.S. Kite in the ice floes off northeastern Newfoundland,

Photo by William Howe Greene. From William Howe Greene, The Wooden Walls Among the Ice Floes. (London: Hutchinson & Co. Ltd., 1933)

In the days of the sailing vessel, virtually every major settlement within the sealing region produced seal oil and prepared hides. These domestic industries declined with the introduction of steamers. Profits were controlled by a few St. John’s firms. Furthermore, as the number of sealers declined and the population of the northeast coast increased, the seal fishery, which had made such a significant contribution to the growth of Newfoundland’s economy throughout the 19th century, diminished greatly in importance. At mid-century, seal products accounted for roughly one-quarter of the island’s exports; 50 years later this had dropped to less than 10 per cent. Even on the northeast coast sealing had become a relatively minor landsmen activity in the traditional annual round.